“There was nowhere to move in my home. Paintings were everywhere—they were becoming part of the furniture!” “I don’t know what painting teaches me, but I know that it frees me.” Carrey, who quickly became obsessed with his hobby, admitted.

“People were wondering where I went,” Jim Carrey said with a laugh.

In case you didn’t know, the actor and comedian is also a talented painter and sculptor, as revealed by I Needed Color, a new short documentary from Signature Gallery Group.

He was calling from his home-turned-art-studio earlier this week in Los Angeles. “The truth is,” he went on, “I was spirited into the forest by a sprite, and you know, you really just follow it when it happens.”

Although he’s taken a backseat as a movie star for the past decade or so, he’s been prolific in other ways. This summer, as mentioned before, a short, six-minute documentary about Carrey’s career as a painter, I Needed Color, surprised everyone and blew the internet’s mind, even though Carrey has in fact been consumed by the pursuit for the last six years, a time span in which his house has been filled with so many paintings he’s used them as furniture, even “eating off” them.

Carrey is shown working in the early morning hours to complete his colorful canvases, sketching out massive compositions with free, easy brushstrokes, pouring paint directly on the surface of his works, and dramatically scraping layers of color. Some of his works are so large that he can only reach the center of the canvas by resting it flat on the ground and propping up a ladder above the painting, working while lying on his stomach.

These days, Carrey’s L.A. home, overgrown with flowers (which in turn house hummingbirds that he likes to call his “landlords”), resembles “a museum, with me as the curator and artist and tour guide,” as he put it when we spoke after a morning of painting. Having just returned from a whirlwind of film festivals from Venice to Toronto to promote his new Netflix documentary, he was getting re-acclimated to the unpredictable and often illogical nature of going viral, after giving a rather existential interview during a stop at New York Fashion Week.

Carrey’s first official exhibition opens at Signature Galleries at the Venetian in Las Vegas this weekend, and its title, “Sunshower,” he made a point to explain, is about witnessing moments like a sun shower or “a beautiful moon” and “being brought into awareness in this present moment, to that part of your consciousness that wants to stop in time and own it.”

And yes, Carrey has been studying mindfulness, as well as Christ consciousness and non-dualism and the Bhagavad Gita, all of which he managed to bring up while also touching on everything from that time his first drawing of Jesus landed him in a fist fight to how he’s feeling about reuniting with Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind director Michel Gondry.

“I was a seeker for a long time, but I’m not seeking anything anymore,” Carrey said. “I feel like I don’t need anchors anymore, because there’s no boat to anchor, and you only need anchors if you have a boat.”

Ladies and gentlemen, meet the new Jim Carrey.

- How did you end up making I Needed Color? Was it part of a conscious decision to make your art more public?

I think it’s just making its own decisions, honestly. People were wondering where I went. [Laughs.] The truth is I was spirited into the forest by a sprite, and you know, you really just follow it when it happens. Creativity just kind of choreographs the dance for me—it sends me the scripts I need when the scripts I need to do are important, and when I’m not vibing with anything, it makes something else happen. That was kind of it; there was a lot exploding in my life. My journey was exploding and I needed to express it, and I needed to express every bit of it.

- Are you talking about what led to making the movie, or making art in general?

Well, making art in general is not really a choice. Even acting—all this stuff is the same thing to me. It’s just different modes of creativity. I’ve always drawn and sketched and done cartoons, and I find myself doing that still—I’m still an eight-year-old in my room. It’s a wonderful feeling to make something out of nothing, and it took me over for a long time; it’s another appendage now, and a huge one. There’s not a day that goes by that I’m not covered in paint or something from doing sculptures. I’ve had a few sculptures happen to me as well in the last while that have revealed different aspects of consciousness and truth to me, even before I intended them to. I just did them, and I kind of got out of the way. It’s the same thing happens for athletes when they’re in the—what do they call it?—the zone. They’re completely engulfed and their attention is completely on one thing: Get the ball, pass it to someone, go. It’s all about that for me now—being completely involved, heart, mind, and soul. Sometimes it’s art, sometimes it’s performance, and sometimes it’s just talking to someone, but there’s very little preparation anymore in anything. I allow things to happen and then they tell me what they meant later.

- You’ve been making art since you were a kid, but it was only six years ago that you decided to start painting?

Well, I didn’t decide; it decided. There was a lot of pain and confusion and everything you need to make something meaningful—circumstances that made me let go and go, Okay, I can risk all that now in order to allow all this energy to come through. It was extremely liberating, and now there’s a feeling of gratitude around it, and pleasant surprise—not only that people are enjoying the work, but that they’re understanding where it comes from. Even though people might call me crazy when I say Fashion Week is meaningless—it’s not the only thing meaningless thing. [Laughs.] Most things are meaningless. But I’m being painted and I’m being expressed and I’m being created, and there’s little me involved. It’s just getting out of the way, and it’s so much fun. Literally last night I had trouble sleeping because there’s a feeling where it’s almost like there’s no body anymore—it’s just a cloud of love and gratitude and energy marinating over the bed. I find myself having to come back into my body to go to sleep; to just go, ‘Okay, well the body needs to sleep now, because you’ve been vibing for an hour and a half.’ [Laughs.] I don’t know what other artists feel, but… I have a painting I’m staring at right now called Mad Elephant that I just did, because that day I felt like a mad elephant, and I realized afterwards that it’s all of us. It’s all of us who feel like we’re not moving forward the way we want to in life because of what other people want. What other people want is like a chain in the ground that you’re easily powerful and large enough to pull out of the ground, but you don’t because of what others will think. And in that way, we’re mad elephants.

- It seems like your art is helping you manage to escape, though.

Yeah. I might barrel through the street fair on the way to freedom. [Laughs.] I’ll be running in the jungle with a couple of darts in my ass. Who knows where I’ll end up.

- [Laughs.] I’ll keep an eye out. You just mentioned other artists, and I was wondering how Maurizio Cattelan ended up being an early visitor to your studio.

Oh, that was so lovely! I admire him greatly; I love his stuff and his humor and his bent on things, so it was really wonderful for him to come look at my stuff and recognize it and see the good in it. There were a couple of pieces he went, ‘I’m not too crazy about that.’ [Laughs.] But he’s entitled to that, and we had a lot of fun.

- What type of people typically come by now that your house is like a museum?

A lot of creative people. I don’t really want to give people’s names, but I have a lot of big athletes come through that want to see certain things, whatever inspires them. A lot of people are buying the materials and paintings now because I’ve chosen to let them go, which to me is like an adoption. I really want them to sync up with someone who’s moved by it. To me, I value the idea of it going out into the world and being part of somebody’s life more than I do hanging onto it. There’s nothing better for an artist than empty walls. They’re extremely motivating. [Laughs.] Just a couple of months ago, I saw a picture of a couple holding the first print I ever sold in a gallery, and holding each other and smiling, and it just made me so happy.

- So it’s only very recently that you’ve been selling your art? “Sunshower” is your first real official showing?

Yeah. And you might not necessarily think about Vegas and art in the same breath, but I love the idea because it gives me an opportunity to not only let people who want to spend money on art see the stuff, but also real people who walk in who might not go into the Gagosian or whatever it is—not that I have that option yet. It’s accessible, and I love that.

- You mentioned well-known athletes coming by recently, and I saw you responded when LeBron James tweeted about your work. Have you two finally met?

Now don’t be trying to sneak in the side door. [Laughs.] I don’t want to say, because I don’t want to use any names, but it’s lovely, it’s just great when you run into people you admire and find out they admire what’s happening with you. It’s just a nice thing. For the most part, there’s a gigantic opportunity in social media, if you can sift through the garbage and baloney. There are teachers and there are great intellects and great discussions, so I use it to go, ‘Gnosticsm, what’s that?’ and start looking. There’s a wealth of knowledge on there—and a lot of baloney, too. The fact is it’s really impossible to know anything at all anymore. There’s so much noise, but it’s entertaining.

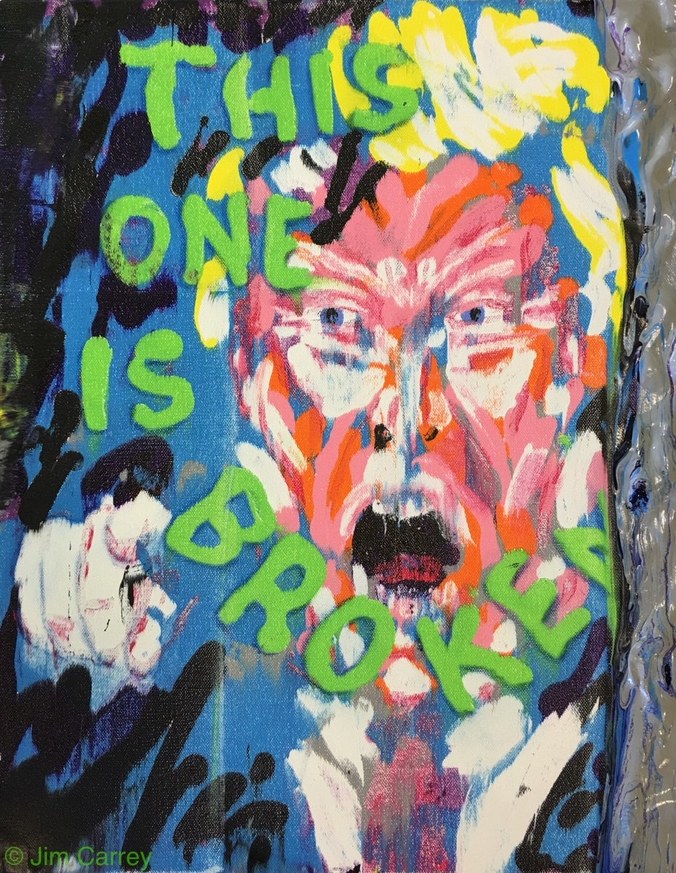

- You’ve also been using Twitter as a platform for your paintings of Donald Trump.

Yeah, I do a lot of political cartoons. I’ve been doing them all along. When I was in grade six, my teacher confiscated a bunch of the cartoons I made in the back of class of her being mutilated by bombs and axes, dogs chewing her leg, whatever. And then she sent them back to me when I got famous. [Laughs.] She’d been saving them; she said she knew something was going on there.

- Do you find it cathartic to paint Trump?

Yeah, I think no one can really escape that aspect of life at this moment—the feeling of loss of control. I’ve given up control in a lot of ways, and kind of the idea of self in general, but I still tweet and draw political cartoons and play the part of Arjuna who has to fight the battle in Bhagavad Gita. It’s not a battle I want to fight, but you’ve got to play a part. Every day at some point there’s pretty much a peaceful acceptance of what’s going on in my life right now, but I do also tune in to the Republican—what could I call on it?—war on logic, intelligence, and compassion at least once a day.

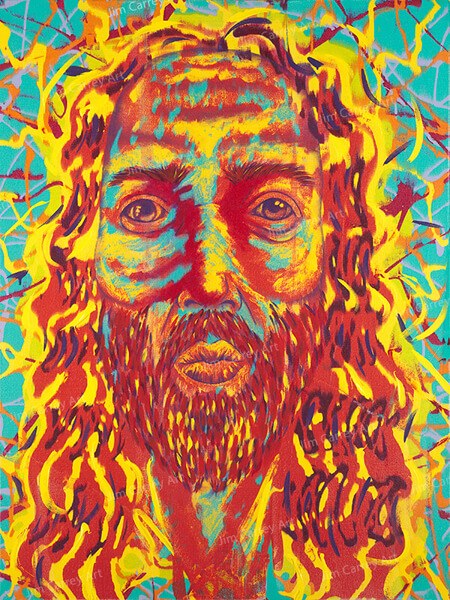

- Another frequent subject of yours is Jesus. You’ve said you’re not sure if he’s real or what he means—do you remember the first time you painted Jesus and why?

I’m not somebody who really believes that we should deify people—I think that’s where the problems begin, when people think they have the right to kill you if you don’t believe them. But I do think that Jesus was a great soul and an amazing teacher, and in that way god, as we all are. I’m not really about the historical person as much as I am the energy behind the person, but he’s constantly coming up in my head. I definitely remember the first time he came up in my work: It was in art class, grade three or four, and because I was in Catholic school, I decided to draw a really beautiful picture of him. I was so proud of it, and I couldn’t wait to bring it home and show my parents, because I’d show them all my art and they’d flip out and throw me the metaphorical dog bone and tell me how special I was. But on the way out of the school yard, some bully got in front of me, and this gang started picking on me for it, saying, ‘You drew a picture of the lord.’ A fight started, and I just remember seeing the picture float through the air between bodies and a mud puddle, because it had been raining, face down. And then I became like a whirling dervish and just started punching faces, any face that I could find. I lost my mind. It was like somebody killed my baby. I don’t remember what happened exactly—all I know is I punched a lot of people that day. [Laughs.] Maybe not the reaction you want, and not the reaction Jesus would have wanted, but it just took over. There was love in that picture, and someone was ruining my art, and I couldn’t have it. I’m a different person now, though—it would still hurt, but I wouldn’t punch them in the face.

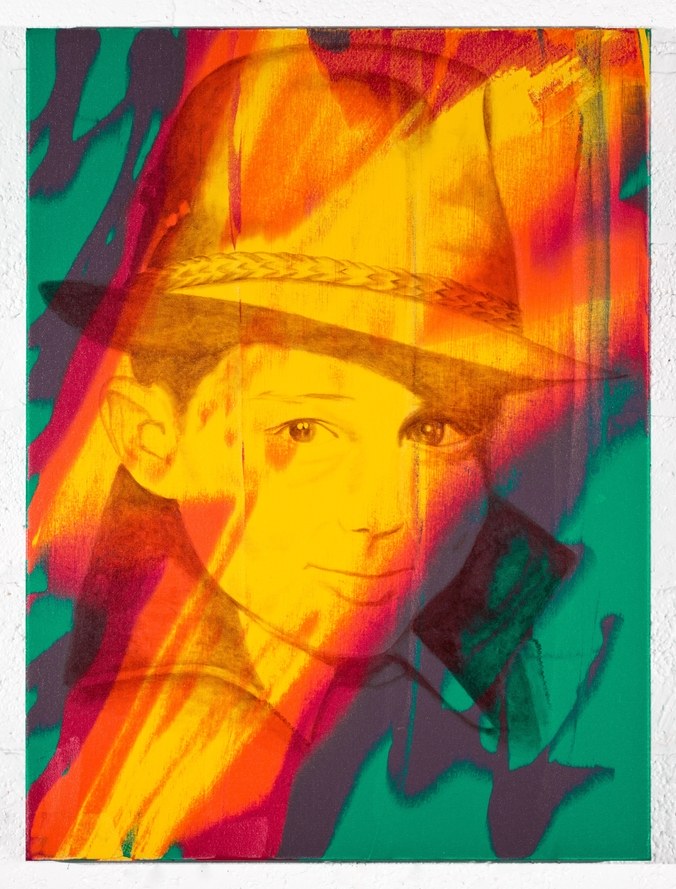

- Recently though, you’ve been saying how you struggled to find yourself again after “Jim & Andy”, the documentary where you go to great lengths to embody Andy Kaufman and Tony Clifton. Is art something that helped you get back to yourself?

No, I’ve gone further and further from my so-called self. I didn’t get back. I did get back to understanding what Jim Carrey is supposed to do and who he’s supposed to be, and then shortly after that the deconstruction of that started to occur, and it’s been occurring more and more ever since. Not that there isn’t a player on the game grid—there definitely is an avatar, and he gets to dress up in fancy clothes and go and act like a personality, and that’s not who I am.

- What have you thought about the internet’s reaction to some of your recent interviews, like the Fashion Week one you mentioned?

I actually am surprised. There’s a lot of surprise around it—pleasant surprise. You know, when you take your mask off, there’s a s— load of people still wearing the mask who are not gonna like that you’re making their mask look like a mask. [Laughs.] But being authentic, you always risk people calling you crazy or thinking you’re having a nervous breakdown. And it’s nothing like that. I’ve never been more calm in my life; if anything, I’m the eye of the hurricane and there’s this force that’s traveling around me, which is wonderful. People often mistake freedom and liberation for crazy. And do I sound crazy to you? I don’t know.

- No, I don’t think so. I definitely agree with some of what you’ve said recently.

Yeah, there are just constructs that people are afraid to let go of. “Oh! What happens if an actor says he’s not special? My god!” [Laughs.] The other night, I found myself at a Broadway show telling the audience they don’t matter, and that’s just not done. I’m not being obstinate, I’m not trying to put them down—I just really don’t think they matter. I don’t think we matter. And to the extent that we just give ourselves a purpose, if anything matters at all, maybe it’s the alleviation of suffering. But that only matters to us—it doesn’t matter to the universe. And we are the universe, so you’re free of this thing. When I went on stage with Michael Moore [during Moore’s Broadway show The Terms of My Surrender earlier in September], I started thinking about it the night before. If you told me even two years ago I’d be on a Broadway stage talking about politics and doing whatever, I would have been preparing for months in advance, but now, I literally just let things roll through my head. I do very little prep or memory work and just get up and just walk out on the stage. It doesn’t get me nuts at all; I just feel like it’s all my living room now, and like I’m the audience, so there’s no division or delineation anymore. There’s nothing at stake. I don’t care what happens, except about connecting in that moment. But it’s weird what happens now—I was just supposed to go out there for 10 minutes but it was half an hour.

- How’d it go in the end?

I had a friend in the audience who I’d spoken with the night before, and he said half of it was things we had discussed. Maybe they rolled through my head and formed themselves into bits in front of the audience, but I literally just dropped all of it and started talking. There was a feeling going through me that I’m not sure that I’m not sure that they were happy about, but here’s the feeling: What I want to give people more than anything else in the world is freedom from themselves, and freedom to be present in the moment. And if I prepare a bunch of stuff to memorize beforehand, I spend that time in the future, and when I hit the stage, I’m in the past trying to remember it, so I’m never present with the audience. I don’t want to be that way. I want to be–whether it’s sloppy or not—fully present.

- You’re about to executive produce a second season of “I’m Dying Up Here”, and star in another Showtime series, “Kidding”, directed by Michel Gondry. How are you feeling about going back to TV more full-time?

I think it’s great and beautiful and bizarre and everything at once. I can’t remember a busier time than right now. I’m so gratified and stoked about I’m Dying Up Here—I think it’s a beautiful show and I love everyone involved, and I’m honored to bring that era to people in a way that’s fairly accurate. And Michel Gondry—being in a creative space with Michel again is a really exhilarating idea. I said to him, If we can do something revolutionary, I’m in. So I’m going to allow whatever happens to happen and try to keep fear out of the mix.

- Have you kept in touch with him since Eternal Sunshine?

Yeah, sure. I saw him in Paris not too long ago and we talked about our lives. We’ve been keeping in touch thinking about what we can do together, and then he jumped into this, and I was like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s a no-brainer, I would do anything for Michel.’

- Are you actually writing a novel right now as well?

Yeah, it’s going to be very special. I don’t want to drill down on exactly what it is, but I can tell you that it’s a completely original idea. And it’s a literary piece; it’s not pulp. I’m writing with a wonderful writer friend named Dana Vachon. We’ve been working on it for several years, and we’re like an old married couple that talk to each other at least twice a day. I’m super excited about what’s going to happen with that; it’s not going to be like anything anybody’s ever seen. I think we’ll probably be publishing it sometime at the turn of the year or end of this year.

- Wow—it’s been quite a busy year for you.

It’s a crazy, amazing space right now. I am the space in which it’s all happening, and it’s wonderful.

- How do you make time for it all? Do you still work on your art at 5 a.m.?

Yeah, whenever. I think some of the greatest days are days when you’re so taken by it that you don’t sleep, or you wake up at four in the morning, and go, Okay, this is when this day starts, and magical things happen. Sometimes you’re just so excited about things, like when I went to Venice. There was a time change to contend with, but also I felt so excited about going out and fronting this documentary [Jim & Andy] and the concepts of consciousness and identity that were being discussed in it, that I found it difficult to sleep—I think I got an hour, after a 15 hour flight. But somehow I was just really energized all day. There was a lot of fandom, though, it’s crazy. It’s ratcheted itself to another level, 10 or 20 times what it used to be, and I don’t know what that’s about, if it’s because of the internet or maybe because I wasn’t there for a while. But it was a really beautiful night and there was a lovely acceptance and honoring of the things I’ve done that’s going on. I feel a weird sense that this person, Jim, was there during people’s childhoods, and they’ve now grown up, and they’re the ones in charge. And their children are being introduced to it, too, so it’s a very wide spectrum of people. There’s a lot of love, and I’m very grateful for it. That’s how I’m feeling about the opening, too; I’ll be getting on a plane with a bunch of good friends and we’ll walk in the door and set off a love bomb, and that’ll be that. Love bomb in Vegas this weekend! [Laughs.] We’ll just enjoy that moment.

Connect with us