Are artificial sweeteners really helping you live healthier, lose weight and satisfy your cravings for sweet at the same time? While diet drinks and low-calorie food that contain non-sugar sweeteners initially seemed like a good idea, evidence is building up that they are not very helpful and that they may even be harmful.

New research has found that artificial sweeteners and many low-calorie foods are doing more harm than good, and actually setting people up for weight gain and metabolic abnormalities.

Public health agencies, such as the American Diabetes Association, continue to support the use of artificial sweeteners and spread incorrect message that they are a sensible alternative to sugar for diabetics, research continues to accumulate to the contrary.

Researchers at the University of Adelaide in Australia revealed in their study that artificial sweeteners weaken the body’s response to glucose, reducing control of blood sugar levels.

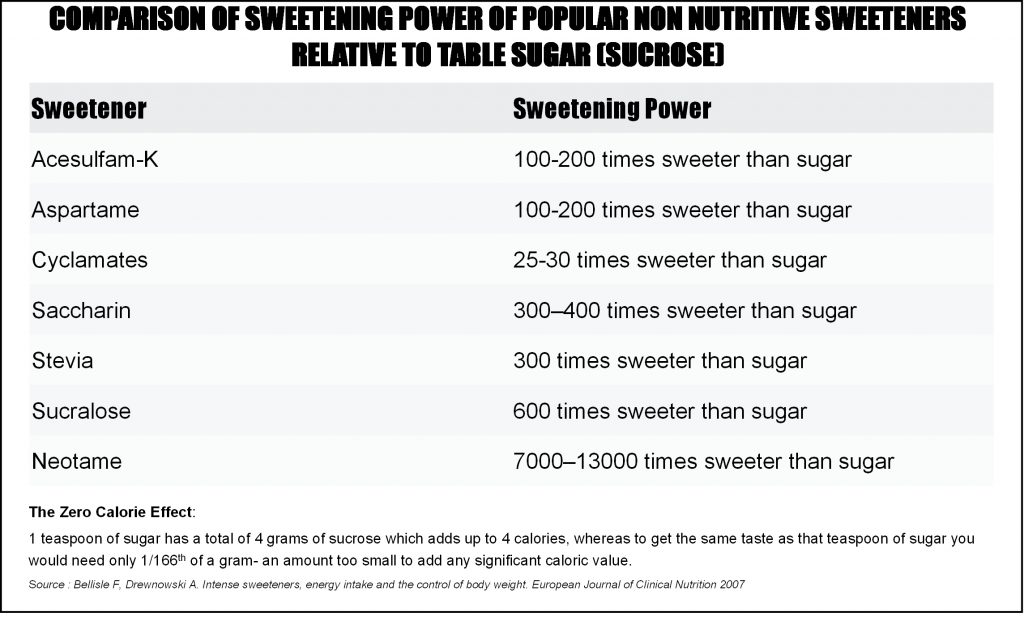

Twenty seven healthy participants were involved in the study, and were given capsules of a) the artificial sweeteners sucralose in an amount equal to consuming 1.5 liters of diet drinks a day or b) placebo.

In only two weeks, the group that received artificial sweetener began showing adverse effects to their blood sugar levels, including a reduction in numbers of the gut peptide, which limits the rise in blood sugar after eating. This means exaggerated rise in the post meal glucose levels, which could ultimately lead to developing Type 2 diabetes among artificial sweeteners users.

Critics of the University of Adelaide study argued that it was impossible to conclude from the data available that the observed changes would lead to diabetes. But it’s not the first study to suggest such a link. For instance, another study showed that drinking aspartame-sweetened diet soda daily increased the risk of Type 2 diabetes by 67 percent (regardless of whether the participants gained weight or not) and the risk of metabolic syndrome by 36 percent.

A report published in the journal Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism also claims that non-caloric artificial sweeteners may increase the risk of weight gain, obesity, metabolic syndrome and other related problems like Type 2 diabetes by inducing “metabolic derangements”.

Glucose intolerance is a condition in which the body loses its ability to cope with high amounts of sugar, and it’s a well-known predecessor to Type 2 diabetes. It also plays a role in obesity, because the excess sugar in our blood ends up being stored in our fat cells. This means obese individuals who use aspartame may have higher blood sugar levels, which in turn will raise insulin levels, leading to weight gain, inflammation and an increased risk of diabetes.

Another evidence against the use of sucralose is a research presented last year at the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Orlando, Florida, which also found that this artificial sweetener promotes metabolic dysfunction that may promote the accumulation of fat.

Sucralose was tested on stem cells from human fat tissue, which revealed that a dose similar to what would be found in the blood of someone who drinks four cans of diet soda a day increased the expression of genes linked to fat production and inflammation, as well as increased fat droplets on cells.

The study’s lead author, Dr. Sabyasachi Sen, associate professor of medicine and endocrinology at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., noted in a press release, “From our study, we believe low-calorie sweeteners promote additional fat formation by allowing more glucose to enter the cells, and promotes inflammation, which may be more detrimental in obese individuals.”

It’s a little-known fact that artificial sweeteners have also been shown to induce glucose intolerance by altering gut flora. Research led by Eran Elinav of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, first showed that mice who were fed artificial sweeteners developed glucose intolerance after 11 weeks. They then revealed that altering the animals’ gut bacteria influenced their glucose response.

But there is also a psychological part of the problem. Psychiatry professor Dana Small from the Yale University says that the sweet taste artificial sweeteners provide, which is many times sweeter than sugar, is not a match of the calories it provides. But our body is designed to relate the two, and the mismatch that occurs leads to the disruptions of the metabolism.

“The assumption that more calories trigger greater metabolic and brain response is wrong. Calories are only half of the equation; sweet taste perception is the other half … Our bodies evolved to efficiently use the energy sources available in nature. Our modern food environment is characterized by energy sources our bodies have never seen before,” explains professor Small.

The study found that an artificially sweetened, lower-calorie drink that tastes sweet can trigger a greater metabolic response than a drink with a higher number of calories. Your body uses the drink’s sweetness to help determine how it should be metabolized. When sweetness matches up with the calories, your brain’s reward circuits are duly satisfied. However, when the sweet taste is not followed by the expected calories, your brain doesn’t get the same satisfying message.

This may explain why diet foods and drinks have been linked to increased appetite and cravings, as well as an increased risk of diabetes and other metabolic diseases. When you eat something sweet, your brain releases dopamine, which activates your brain’s reward center. The appetite-regulating hormone leptin is also released, which eventually informs your brain that you are “full” once a certain amount of calories have been ingested.

However, when you consume something that tastes sweet but doesn’t contain any calories, your brain’s pleasure pathway still gets activated by the sweet taste, but there’s nothing to deactivate it, since the calories never arrive. Artificial sweeteners basically trick your body into thinking that it’s going to receive sugar (calories), but when the sugar doesn’t come, your body continues to signal that it needs more, which results in carb cravings.

One more doctor at Yale University School of Medicine, the cardiologist Dr. Harlan Krumholz admits that he, as many Americans, drank diet drinks since he believed that the low-calorie, sugar-free drinks are a guilt-free source of caffeine that helped him keep his weight down. Now he feels betrayed, and he’s speaking out against them. Krumholz cites that the evidence from researches do not clearly support the intended benefits of nonnutritive sweeteners for weight management, and observational data suggest that routine intake of nonnutritive sweeteners may be associated with increased body mass index and cardiometabolic risk.

Another, conducted by his Yale University colleagues, found artificial sweeteners “are not physiologically inert compounds” and may “impact energy balance and metabolic function, including actions on oral and extra-oral sweet taste receptors, and effects on metabolic hormone secretion, cognitive processes (e.g., reward learning, memory, and taste perception), and gut microbiota.”

Krumholz wrote in The Wall Street Journal that he’s stopped using diet drinks is removing them from the rest of his diet as well.

“It is reasonable to ask why these substances were not evaluated as drugs in the first place,” he says. “Millions of people are exposed to them every day, and yet their long-term effect is uncertain. Could they be actually causing the health problems they were intended to prevent? I don’t know the answer at this point, but it seems to me that the burden of proof is on the manufacturers to show benefit and demonstrate safety through clinical trials … If, in the end, we discover that large-scale consumption of diet drinks and foods helped fuel the obesity epidemic, it would be more than ironic. It would be tragic.”

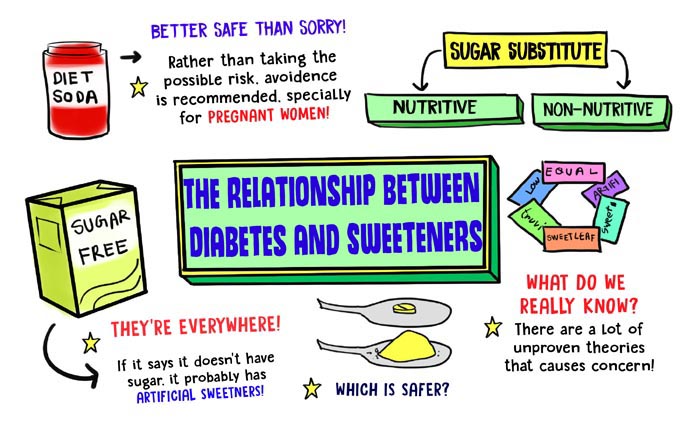

If you’re an artificial sweetener fan or even if you consume them moderately, it seams as a smart move for your health to remove them from your diet. Just be aware that they’re found not only in diet sodas but also in many low-calorie and reduced-calorie foods, from yogurt and ice cream to bread and salad dressing.

And we should learn from Dr. Krumholzs’ discovery that we cannot simply trust that companies are producing and advertising good food for us and that it is essential to read the labels and understand ingredients of the food and drinks we consume.

Connect with us